From the Journal

When Did The Dodo Go Extinct? The Complete Story

The haunting tale of the Dodo's extinction stands as one of history's most profound lessons in conservation. While we can pinpoint the last verified sighting to 1662, the story of how this remarkable bird vanished forever is far more complex than a simple date.

The Last Dodos

The final confirmed sighting of a living Dodo came from Dutch sailor Volkert Evertsz, who encountered the bird on Amber Island off Mauritius's coast in 1662.

While unverified reports persisted until 1688, most experts agree the species vanished from Earth before 1700 - marking one of the swiftest documented extinctions of a large vertebrate.

First Contact and Swift Decline

The Dodo's story with humans began in 1598 when Dutch sailors first spotted these "foules twise as bigge as swans" on Mauritius. The birds' trusting nature, born from millions of years without predators, initially charmed visitors.

Sailors described them as peaceful giants, approaching humans without fear - a behaviour that would prove fatal.

Got a photo of a bird you can't identify?

Upload a photo and find out what it is in seconds — no account needed

Identify a BirdWhy Did They Vanish So Quickly?

The Dodo's extinction wasn't simply a result of hunting, though that played a part. Rather, it was a perfect storm of threats:

Direct Human Impact

- Hunting by sailors and settlers

- Habitat destruction for settlements

- Collection of specimens for European curiosity cabinets

Introduced Species

- Rats, pigs, and monkeys raiding nests and eating eggs

- Dogs and cats hunting adult birds

- Invasive deer and livestock damaging native forests

Evolutionary Disadvantages

- Single-egg clutches limiting population recovery

- Ground-nesting behaviour exposing eggs to predators

- Lack of fear toward humans and other predators

Modern Understanding

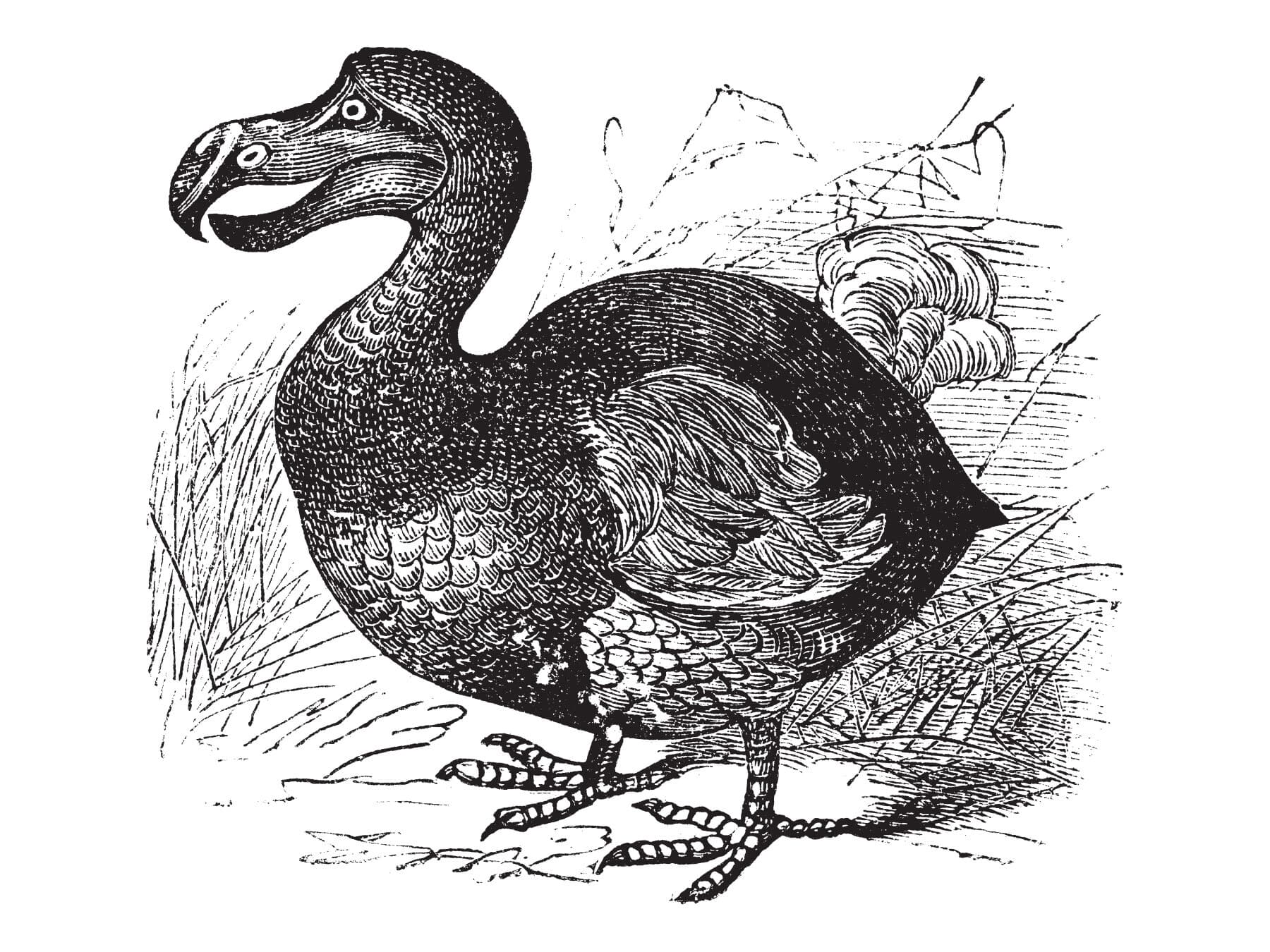

Recent scientific analysis has reshaped our understanding of the Dodo. Far from the popular image of a plump, awkward bird, skeletal studies reveal a well-adapted island species.

Their supposed stupidity was actually "ecological naiveté" - a common trait among isolated island species that evolved without predators.

Legacy and Lessons

The Dodo's extinction marked a turning point in human understanding of our impact on nature. As one of the first documented human-caused extinctions, it continues to serve as a powerful symbol of conservation.

The phrase "dead as a dodo" entered the common language, carrying a warning about the permanence of extinction.

Archaeological Evidence

The limited physical evidence we have of Dodos makes their story even more poignant:

- Only two relatively complete skeletons exist

- The last complete stuffed specimen burned in 1755

- Surviving soft tissue samples are limited to a head and foot

- Contemporary illustrations vary widely in accuracy

Modern Conservation Impact

The Dodo's story has profoundly influenced modern conservation efforts. Its extinction demonstrates how quickly isolated island species can vanish and highlights the devastating impact of introduced species.

Today, Mauritius leads groundbreaking conservation programs to protect its remaining endemic species, learning from the lessons of the Dodo's extinction.

The value of the Dodo lies not just in its fascinating history but in what it teaches us about conservation. Its story continues to influence how we think about species protection, island ecosystems, and our responsibility to preserve Earth's biodiversity.

Identify Any Bird Instantly

- Upload a photo from your phone or camera

- Get an instant AI identification

- Ask follow-up questions about the bird

Monthly Birds in Your Area

- Personalised for your location

- Seasonal tips and garden advice

- Updated every month with new species