From the Journal

How Do Birds Breathe? (Everything Explained)

A bird’s respiratory system is somewhat different to that of a human, and needs to work efficiently, even at higher altitudes where the air has lower oxygen levels. In order to sustain flight, a constant supply of oxygen needs to reach a bird’s muscles and bloodstream.

But just how does a bird’s respiratory system work? Keep reading as we take a closer look at how birds breathe.

Air flows into a bird’s body through nostril-like openings on the beak, moving through the trachea, posterior air sacs, lungs, and anterior air sacs, and passes out again through the trachea. Gaseous exchange takes place in the lungs, where carbon dioxide is exchanged for fresh oxygen.

Birds need a constant supply of a higher volume of oxygen than humans, and the two-directional airflow system used in human lungs and alveoli would not provide a bird with the amount of oxygen it requires to maintain its ultra-fast metabolic rate.

A bird’s respiratory system takes up around 20 percent of their internal volume, in contrast to around 5 percent in humans, but the network of lungs and air sacs work efficiently to supply a bird with enough fresh oxygen to be able to fly and sing at the same time!

Please read on to discover more about bird respiration and how it takes two breaths, rather than just one, for air to circulate through the air sacs and lungs of a bird’s respiratory system.

How does a bird respiratory system work?

Respiration in birds begins at the nares, tiny openings on either side of the base of the beak that provide a similar function to nostrils (for kiwis, these openings are at the tip of the bill instead).

From these openings, the air that is breathed in travels through the bird’s trachea to a network of air sacs and lungs in one direction, before passing back out through the trachea.

By taking a look at the respiratory cycle, and each of its components in turn, we can get to grips with the full ins and outs of bird breathing.

Respiratory cycle

A bird takes two breaths to complete one full cycle of breathing. Here’s a summary of how it works:

- Inhalation: Air flows in through the nostrils, moves through the trachea, and fills the posterior air sacs.

- Exhalation: Air leaves the posterior air sacs and travels into the lungs, moved by the contraction of muscles in the ribcage. Gaseous exchange takes place in the lungs, where the waste carbon dioxide is swapped for fresh oxygen.

- Inhalation: Air leaves the lungs, flowing into the anterior air sacs.

- Exhalation: Air passes from the anterior air sacs into the trachea, leaving the beak through the nostrils.

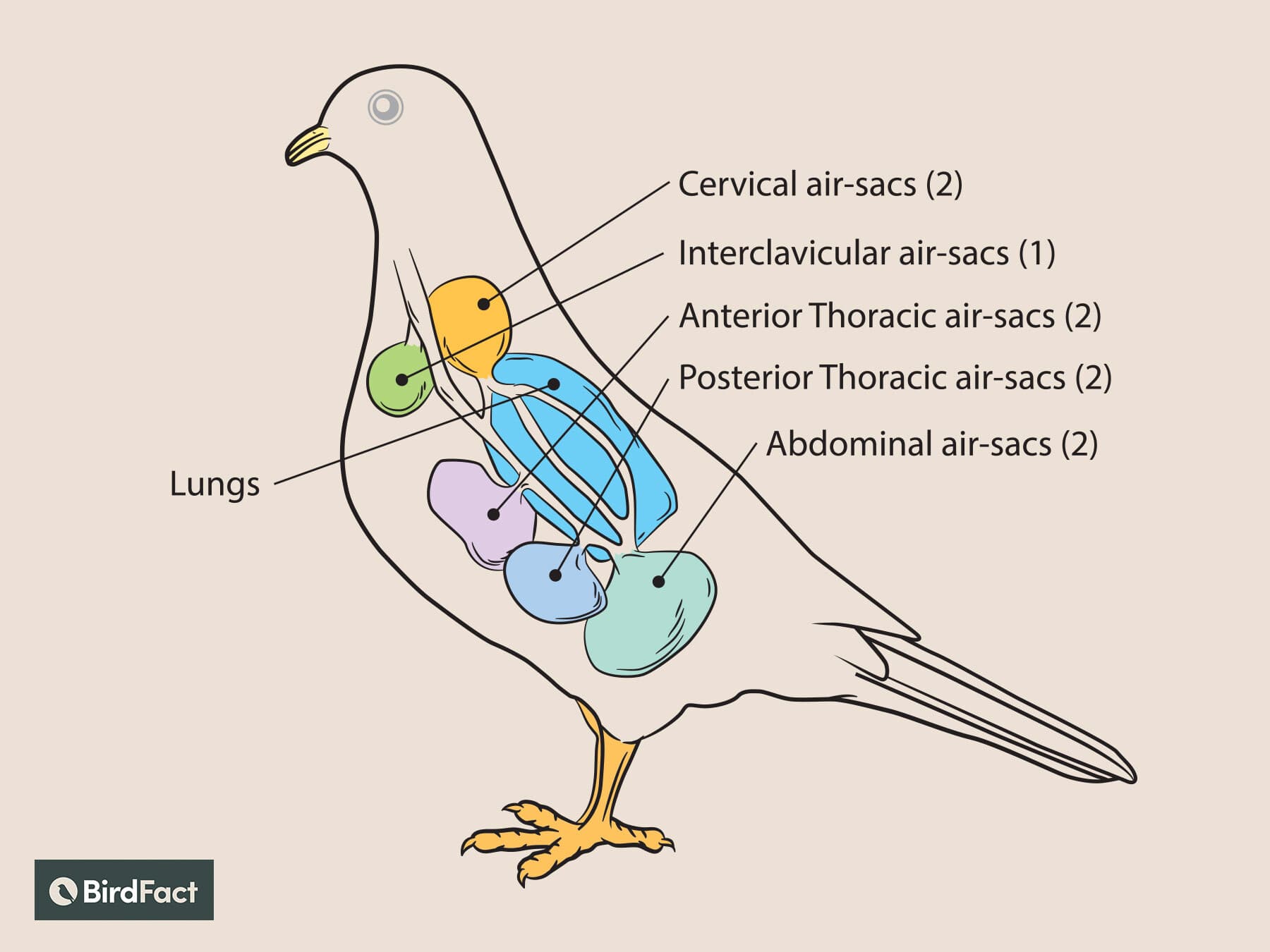

Air sacs

Most birds have a total of nine air sacs: four pairs of air sacs (posterior: two abdominal, two posterior; anterior: two anterior, two cervical) plus a single, unpaired (interclavicular) sac. Freshly inhaled air enters the posterior air sacs before it is transferred to the lungs, and then moves to the anterior air sacs, before passing out of the trachea.

Lungs

A bird’s lungs are kept constantly inflated by the air sacs, which act in a similar way to bellows. Lungs serve the vital purpose of bringing oxygen into the bloodstream to meet the bird’s metabolic needs, and removing waste carbon dioxide from the bird’s body via a gaseous exchange process. This gaseous exchange process between the lungs and the blood takes place in tubelike structures, known as Parabronchi.

How do birds breathe without a diaphragm?

Human respiration relies on a diaphragm to move air into and out of the lungs. A bird’s respiratory system functions in a different way, using muscle movements to expand and contract its body cavity, causing the air to flow through the system of lungs and air sacs.

Got a photo of a bird you can't identify?

Upload a photo and find out what it is in seconds — no account needed

Identify a BirdDo birds have lungs?

Birds have two lungs that are relatively small in size. These rigid lungs are kept inflated by the flow of air through a network of air sacs. A bird’s respiratory system works efficiently to ensure the bird’s lungs are constantly supplied with fresh air via tubelike structures called Parabronchi, which allow sufficient oxygen to freely enter the bloodstream.

How do birds breathe while flying?

Oxygen consumption of a flying bird is significantly higher than a resting bird. While flying, birds adapt their respiration rate so that they breathe more times per minute, rather than needing to take in more air.

Can birds hold their breath?

Waterbirds, such as cormorants, terns, auks, and gannets, regularly need to hunt for fish beneath the surface of a lake or the sea.

Although they are unable to breathe underwater, they are adapted for diving and swimming by having more oxygenated blood, and can hold their breath for short periods without needing to take in extra oxygen.

Certain duck species can dabble with their heads submerged for short periods of time before needing to resurface and take a breath.

Based on research, it is understood that non-aquatic birds are unable to consciously control their breathing in the same way that humans can, and are unable to hold their breath for extended periods due to the need to constantly be removing carbon dioxide from the blood by the respiratory process.

How long can birds hold their breath for?

Several species of aquatic birds can hold their breath for a significant amount of time underwater, enabling them to dive and swim deep beneath the water’s surface to seek and catch prey. These birds can hold their breath for between 3 and 10 minutes before needing to resurface to breathe again.

One example of a seabird that spends extended periods of time deep in ocean waters hunting fish is the gannet, which has evolved to have no external nostrils on its beak, with its respiratory system openings located in its mouth instead. Gannets can swim for more than 15 minutes underwater without needing to breathe.

How do birds breathe while sleeping?

Breathing is an involuntary action for birds, and continues to follow the regular respiration cycle, regardless of whether a bird is awake or asleep. Resting birds have lower oxygen demands than birds in flight, so their respiration rate will naturally be lower.

Many bird species tuck their beak into their back or wing feathers while sleeping to conserve body heat and maintain their temperature.

Tucking their nares (nostril-like structures on a bird’s beak) close to its body allows a bird to breathe in air warmed by its own body heat, and maintain a stable temperature while sleeping.

How many times per minute do birds breathe?

On average, a resting human breathes around 12 times per minute. For birds, the rate differs from species to species and is lower for birds with a higher body mass. Larger birds such as buzzards take 18 breaths per minute, while canaries need to breathe between 60 and 100 times. Ostriches have a resting breathing rate of only 5 or 6 times each minute.

Do birds breathe through their beaks?

On either side of the base of a bird’s beak are two tiny openings, known as nares. These effectively function in the same way as nostrils, forming the external entrance to a bird’s respiratory system. Air flows into the bird’s trachea through these openings in the beak, before moving to the air sacs and passing into the lungs.

Do birds have gills?

Birds do not have gills. Even aquatic birds that spend a lot of time underwater, such as penguins, do not have gills. Instead all birds breathe by taking in oxygen from the air using their lungs and air sacs.

Identify Any Bird Instantly

- Upload a photo from your phone or camera

- Get an instant AI identification

- Ask follow-up questions about the bird

Monthly Birds in Your Area

- Personalised for your location

- Seasonal tips and garden advice

- Updated every month with new species